Wonder UnderWonder Under is inspired by the ancient sea life of Africa, referencing both the bountiful beauty of sea flora and a celebration of the African sea goddesses who reside there. The work here is about the dual nature of water; its abilities to r... |

Palace Of The PeacockPalace Of The Peacock is a homage to the enslaved women who resisted enslavement by the use of poison. I came across the work of botanist Maria Sibylla Me... |

A Dark CloudThere is a dark cloud at the top of this globe representing the pain and suffering of Africans, forcibly uprooted from their homes and enslaved. It also represents the dark cloud hanging over our history; how the Transatlantic Trade in Enslaved Africans has been historically misrepresented... |

Helix (We Don’t Move In Circles)For most Black people from Africa and the diaspora, a long strand of natural hair forms a helix – like the curved path of a spiral stairway. Yet this helix of hair also can evoke those profound structures which shape the patterns of life. At the microscopic scale is the double helix o... |

No Future Without UCharacters reimagined and futures unknown. This piece is a colourful representation of all that is colourful and Black. The moments of joy we deserve and... |

Catherine's design responds to the theme ‘Mother Africa’, which explores the richness and reality of Africa before the Transatlantic Trade in Enslaved Africans; the impact of the Transatlantic Trade in Enslaved Africans and European colonialism on Africa; and considers and celebrates Africa’s present and future.

Wonder Under is inspired by the ancient sea life of Africa, referencing both the bountiful beauty of sea flora and a celebration of the African sea goddesses who reside there. The work here is about the dual nature of water; its abilities to renew and cleanse, alongside its capacity to destroy and take away anything in its way. With Mother Africa being the birthplace of humanity, we enter into the waters that hold the imprint memory of all time and all that has passed through it.

A layered sea map, connecting and overlapping boundary lines, with reference to the movement of people and these complex layers of history. As we navigate through the unknown waters, the essence of healing is reflected through the work within the colours chosen.

The figures within the work reveal themselves the closer you look, immersed within their surroundings, and very much part of it. The waters allow us to re-enter this space of wonder, and contain everything, enabling us to let go of anything we hold onto, whether that be trauma or desire; the water washes it away, as the sea goddesses take us on a journey of rediscovery.

A Margate-based multidisciplinary artist with a strong focus on large-scale paintings, both indoors and outside. The work can be described as both figurative and socially surreal. Catherine also works with sound and moving image in a collage type of way, connecting footage/sound at random.

Catherine's design responds to the theme ‘Mother Africa’, which explores the richness and reality of Africa before the Transatlantic Trade in Enslaved Africans; the impact of the Transatlantic Trade in Enslaved Africans and European colonialism on Africa; and considers and celebrates Africa’s present and future.

Wonder Under is inspired by the ancient sea life of Africa, referencing both the bountiful beauty of sea flora and a celebration of the African sea goddesses who reside there. The work here is about the dual nature of water; its abilities to renew and cleanse, alongside its capacity to destroy and take away anything in its way. With Mother Africa being the birthplace of humanity, we enter into the waters that hold the imprint memory of all time and all that has passed through it.

A layered sea map, connecting and overlapping boundary lines, with reference to the movement of people and these complex layers of history. As we navigate through the unknown waters, the essence of healing is reflected through the work within the colours chosen.

The figures within the work reveal themselves the closer you look, immersed within their surroundings, and very much part of it. The waters allow us to re-enter this space of wonder, and contain everything, enabling us to let go of anything we hold onto, whether that be trauma or desire; the water washes it away, as the sea goddesses take us on a journey of rediscovery.

A Margate-based multidisciplinary artist with a strong focus on large-scale paintings, both indoors and outside. The work can be described as both figurative and socially surreal. Catherine also works with sound and moving image in a collage type of way, connecting footage/sound at random.

Fiona's design responds to the theme ‘The Reality of Being Enslaved’, which makes real the experience of those people who were enslaved, from their capture, captivity and voyage to lives and deaths enslaved in different contexts, places and generations.

Palace Of The Peacock is a homage to the enslaved women who resisted enslavement by the use of poison.

I came across the work of botanist Maria Sibylla Merian – who travelled to the Dutch Guianas in the 1700s – and amongst her beautiful drawings and descriptions of the flora and fauna of Suriname, was a short passage describing the peacock flower. I was struck by both the beauty and tragedy of this unexpected passage - especially the language used – that the enslaved women were ‘threatening’ to refuse to have children. They understood the value of their bodies, hence their refusal to enrich the pockets of slave owners by way of the suffering of their children.

Uncovering the complicated history of women’s agency of their own bodies under chattel enslavement, this piece aims to draw in viewers through the use of the bright beauty of the peacock flower. Interwoven between the peacock flower lies two key elements, the cassava flower, which was a plant root used to create another poison used by the enslaved to poison their masters in resistance. An integral element of the diet of enslaved on plantations, its natural accessibility gave the opportunity for enslaved to take control over their own lives by way of poison.

The second element interwoven into the flowers is the names of enslaved people across the Caribbean who were executed in brutal and horrific ways for poisoning their masters. Instances where these people risked death in the hopes of freedom, even if it is freedom of choice over their bodies. The title of the piece comes from the novel by Guyanese writer Wilson Harris, which tells the story of a woman who escapes from the clutches of a cruel European colonist.

This globe aims to be dichotomous through the beauty of the bright and joyous flowers, with the tragedy and triumph of these women who made the ultimate sacrifice in the quest for freedom.

Fiona Compton is a London based Saint Lucian photographer, artist, filmmaker and historian. After graduating from London College of Printing in 2005 with a BA in photography, Fiona has been working as a professional photographer, working for the UK’s largest publishing houses, travelling between the UK and Europe to photograph some of the most influential figures in the world of Finance and Banking. Over the past 13 years her work has explored the various disparities in representation of the Afro Caribbean diaspora within art and mainstream media. In 2017 she launched her multi disciplinary project ‘The Revolution of the Fairytale’ which celebrates lesser known heroes from Black History under the nostalgic platform of well known fairy tales. Fiona remains a strong advocate for her history and culture and is an Official Ambassador for London’s Notting Hill Carnival, the second largest street festival in the world.

Fiona's design responds to the theme ‘The Reality of Being Enslaved’, which makes real the experience of those people who were enslaved, from their capture, captivity and voyage to lives and deaths enslaved in different contexts, places and generations.

Palace Of The Peacock is a homage to the enslaved women who resisted enslavement by the use of poison.

I came across the work of botanist Maria Sibylla Merian – who travelled to the Dutch Guianas in the 1700s – and amongst her beautiful drawings and descriptions of the flora and fauna of Suriname, was a short passage describing the peacock flower. I was struck by both the beauty and tragedy of this unexpected passage - especially the language used – that the enslaved women were ‘threatening’ to refuse to have children. They understood the value of their bodies, hence their refusal to enrich the pockets of slave owners by way of the suffering of their children.

Uncovering the complicated history of women’s agency of their own bodies under chattel enslavement, this piece aims to draw in viewers through the use of the bright beauty of the peacock flower. Interwoven between the peacock flower lies two key elements, the cassava flower, which was a plant root used to create another poison used by the enslaved to poison their masters in resistance. An integral element of the diet of enslaved on plantations, its natural accessibility gave the opportunity for enslaved to take control over their own lives by way of poison.

The second element interwoven into the flowers is the names of enslaved people across the Caribbean who were executed in brutal and horrific ways for poisoning their masters. Instances where these people risked death in the hopes of freedom, even if it is freedom of choice over their bodies. The title of the piece comes from the novel by Guyanese writer Wilson Harris, which tells the story of a woman who escapes from the clutches of a cruel European colonist.

This globe aims to be dichotomous through the beauty of the bright and joyous flowers, with the tragedy and triumph of these women who made the ultimate sacrifice in the quest for freedom.

Fiona Compton is a London based Saint Lucian photographer, artist, filmmaker and historian. After graduating from London College of Printing in 2005 with a BA in photography, Fiona has been working as a professional photographer, working for the UK’s largest publishing houses, travelling between the UK and Europe to photograph some of the most influential figures in the world of Finance and Banking. Over the past 13 years her work has explored the various disparities in representation of the Afro Caribbean diaspora within art and mainstream media. In 2017 she launched her multi disciplinary project ‘The Revolution of the Fairytale’ which celebrates lesser known heroes from Black History under the nostalgic platform of well known fairy tales. Fiona remains a strong advocate for her history and culture and is an Official Ambassador for London’s Notting Hill Carnival, the second largest street festival in the world.

| The Rialto |

The work of making racial justice a reality must be rooted in community – in our individual and collective experiences, hopes and contributions. Amber's design was created in response to dialogue and workshops with local communities.

Film by: Amber Akaunu

Featuring: Elliss Thompson & Elias Dubicki

Production Assistants: Morayo Omotesho & Arel Akaunu

After engaging with the community in Liverpool City Region, several themes were raised in our discussions. One of these themes was this idea of connectivity between people and places. The discussion went deeper than the physical and touched on unseen and spiritual connectivity. I came away from these discussions inspired and with lots to think about. I decided to represent this idea, and other topics we discussed, through the concept of auras. To align this piece with my own creative practice, I also decided to create a short film piece featuring two creatives from Liverpool. The film, and the globe, embodies the unseen impacts of trauma and enslavement through the visual aura a place has. The film uses colour as a metaphor and gateway to think about these lasting, unseen consequences.

Amber Akaunu (b.1996) is a Liverpool born Nigerian-German filmmaker working in cinema, art, and tv to document and explore Black culture, identity, and history. Amber is a BAFTA scholar and recent MA film graduate who is currently residing in South London. Her creative practice extends to her role as co-founder and editor of ROOT-ed Zine where she works to support Black, Asian and PoC artists in the North West of England through publishing, workshops, guest lectures, curating, and producing.

The work of making racial justice a reality must be rooted in community – in our individual and collective experiences, hopes and contributions. Amber's design was created in response to dialogue and workshops with local communities.

Film by: Amber Akaunu

Featuring: Elliss Thompson & Elias Dubicki

Production Assistants: Morayo Omotesho & Arel Akaunu

After engaging with the community in Liverpool City Region, several themes were raised in our discussions. One of these themes was this idea of connectivity between people and places. The discussion went deeper than the physical and touched on unseen and spiritual connectivity. I came away from these discussions inspired and with lots to think about. I decided to represent this idea, and other topics we discussed, through the concept of auras. To align this piece with my own creative practice, I also decided to create a short film piece featuring two creatives from Liverpool. The film, and the globe, embodies the unseen impacts of trauma and enslavement through the visual aura a place has. The film uses colour as a metaphor and gateway to think about these lasting, unseen consequences.

Amber Akaunu (b.1996) is a Liverpool born Nigerian-German filmmaker working in cinema, art, and tv to document and explore Black culture, identity, and history. Amber is a BAFTA scholar and recent MA film graduate who is currently residing in South London. Her creative practice extends to her role as co-founder and editor of ROOT-ed Zine where she works to support Black, Asian and PoC artists in the North West of England through publishing, workshops, guest lectures, curating, and producing.

Caroline's design responds to the theme ‘Stolen Legacy: The Rebirth of a Nation’, which brings to life how Britain was transformed and enriched as a result of the Transatlantic Trade in Enslaved Africans and the free labour of the enslaved. It explores the legacy of the Transatlantic Trade in Enslaved Africans in building the financial and trading power of Britain; strengthening the Church and the might of universities; and establishing dynastic influence and power.

There is a dark cloud at the top of this globe representing the pain and suffering of Africans, forcibly uprooted from their homes and enslaved. It also represents the dark cloud hanging over our history; how the Transatlantic Trade in Enslaved Africans has been historically misrepresented and Britain's significant role in the trade’s creation. The rain has been created using cotton threads dipped in paint and then printed onto the globe, highlighting the use of slavery within the cotton industry.

The numbers around the globe show the estimated numbers of people taken and enslaved from the different regions of Africa. The colour purple has been used because in the Catholic Church it represents sorrow and suffering and here it highlights the church’s role in slavery.

There are four hundred swallows on the globe representing the four hundred year span of the trade in enslaved Africans. Swallows migrate across the Atlantic and thousands die on the journey due to exhaustion and starvation. However swallows are also often depicted as a symbol of hope, and as you walk around the globe the colours turn to lighter tones reflecting hope for a brighter future and for racial justice and equality.

Caroline is an artist from Manchester with a background in Theatre Design, who is often inspired by wildlife and prefers to work by hand using traditional mediums. Her murals and paintings can be seen on public walls, shop fronts, shutters and sculptures within Greater Manchester and her fine art prints are sold in many gift shops and galleries in the UK. Caroline also enjoys working as an arts facilitator providing a whole host of art workshops for young people and community groups within the North West of England, specialising in mural painting and willow lantern making for community festivals and parades.

Caroline's design responds to the theme ‘Stolen Legacy: The Rebirth of a Nation’, which brings to life how Britain was transformed and enriched as a result of the Transatlantic Trade in Enslaved Africans and the free labour of the enslaved. It explores the legacy of the Transatlantic Trade in Enslaved Africans in building the financial and trading power of Britain; strengthening the Church and the might of universities; and establishing dynastic influence and power.

There is a dark cloud at the top of this globe representing the pain and suffering of Africans, forcibly uprooted from their homes and enslaved. It also represents the dark cloud hanging over our history; how the Transatlantic Trade in Enslaved Africans has been historically misrepresented and Britain's significant role in the trade’s creation. The rain has been created using cotton threads dipped in paint and then printed onto the globe, highlighting the use of slavery within the cotton industry.

The numbers around the globe show the estimated numbers of people taken and enslaved from the different regions of Africa. The colour purple has been used because in the Catholic Church it represents sorrow and suffering and here it highlights the church’s role in slavery.

There are four hundred swallows on the globe representing the four hundred year span of the trade in enslaved Africans. Swallows migrate across the Atlantic and thousands die on the journey due to exhaustion and starvation. However swallows are also often depicted as a symbol of hope, and as you walk around the globe the colours turn to lighter tones reflecting hope for a brighter future and for racial justice and equality.

Caroline is an artist from Manchester with a background in Theatre Design, who is often inspired by wildlife and prefers to work by hand using traditional mediums. Her murals and paintings can be seen on public walls, shop fronts, shutters and sculptures within Greater Manchester and her fine art prints are sold in many gift shops and galleries in the UK. Caroline also enjoys working as an arts facilitator providing a whole host of art workshops for young people and community groups within the North West of England, specialising in mural painting and willow lantern making for community festivals and parades.

Kimathi's design responds to the theme ‘Expanding Soul’, which celebrates the spirit and culture of the African diaspora that, even in the face of incredible suffering, has endured and found vibrant expression across the world in music, art, food and so much more.

For most Black people from Africa and the diaspora, a long strand of natural hair forms a helix – like the curved path of a spiral stairway. Yet this helix of hair also can evoke those profound structures which shape the patterns of life. At the microscopic scale is the double helix of DNA — two molecular strands entwined around one another like lovers. But, on a cosmic scale, the helix could also represent the world’s path through space. Whilst Earth’s orbit of the sun is a slight ellipse, the sun itself revolves around the galaxy, which means that the real path of our planet is not a flat ellipse at all.

Relative to the universe, Earth dances a gloriously curly, kinky helix – indeed, a gargantuan fractal set of ‘meta-helices’ as galactic clusters fall into one another through the twinkling blackness. Which brings us back to hair. Having observed the twisting paths of constellations and polymers, could we consider our hair as a metaphor for our long – often torturous – historical journeys that might seem to go around in circles, but which in truth perform an open-ended, infinitely extended looping motion towards a destination about which we know precious little? Could the helix of Black hair represent an odyssey that can never, will never – must never – return and recirculate through the ‘same places’, such as the evil auction block or whipping post.

Finally, it is said that all the infinitesimal subatomic particles which constitute our reality can be described by what physicists and mathematicians call ‘string theory’. And how are we to imagine those hypothetical strings of energy? Never at rest, flat, straight, or dead. But, constantly in a flux of oscillating vibration through multiple incomprehensible dimensions. Curvaceous, flickering, helices. The whirled, reimagined through the painting of Black hair.

Kimathi Donkor’s art re-imagines mythic, legendary, historical and everyday encounters across Africa and its global Diasporas, principally in painting and drawing. Prominent exhibitions include War Inna Babylon at the ICA, London 2021, the Diaspora Pavilion (57th Venice Biennale, 2017) and the 29th São Paulo Biennial (Brazil, 2010). His awards, residencies and commissions include the 2011 Derek Hill Painting Scholarship for The British School at Rome.

Kimathi's design responds to the theme ‘Expanding Soul’, which celebrates the spirit and culture of the African diaspora that, even in the face of incredible suffering, has endured and found vibrant expression across the world in music, art, food and so much more.

For most Black people from Africa and the diaspora, a long strand of natural hair forms a helix – like the curved path of a spiral stairway. Yet this helix of hair also can evoke those profound structures which shape the patterns of life. At the microscopic scale is the double helix of DNA — two molecular strands entwined around one another like lovers. But, on a cosmic scale, the helix could also represent the world’s path through space. Whilst Earth’s orbit of the sun is a slight ellipse, the sun itself revolves around the galaxy, which means that the real path of our planet is not a flat ellipse at all.

Relative to the universe, Earth dances a gloriously curly, kinky helix – indeed, a gargantuan fractal set of ‘meta-helices’ as galactic clusters fall into one another through the twinkling blackness. Which brings us back to hair. Having observed the twisting paths of constellations and polymers, could we consider our hair as a metaphor for our long – often torturous – historical journeys that might seem to go around in circles, but which in truth perform an open-ended, infinitely extended looping motion towards a destination about which we know precious little? Could the helix of Black hair represent an odyssey that can never, will never – must never – return and recirculate through the ‘same places’, such as the evil auction block or whipping post.

Finally, it is said that all the infinitesimal subatomic particles which constitute our reality can be described by what physicists and mathematicians call ‘string theory’. And how are we to imagine those hypothetical strings of energy? Never at rest, flat, straight, or dead. But, constantly in a flux of oscillating vibration through multiple incomprehensible dimensions. Curvaceous, flickering, helices. The whirled, reimagined through the painting of Black hair.

Kimathi Donkor’s art re-imagines mythic, legendary, historical and everyday encounters across Africa and its global Diasporas, principally in painting and drawing. Prominent exhibitions include War Inna Babylon at the ICA, London 2021, the Diaspora Pavilion (57th Venice Biennale, 2017) and the 29th São Paulo Biennial (Brazil, 2010). His awards, residencies and commissions include the 2011 Derek Hill Painting Scholarship for The British School at Rome.

Sumuyya's design responds to the theme ‘Reimagine the Future’, which gives us free rein to imagine the society we can create when we have a full understanding of our shared history; the place the UK can hold in the world when it acknowledges its past; and who we can be as people and a country when we give full dignity to all.

Characters reimagined and futures unknown.

This piece is a colourful representation of all that is colourful and Black. The moments of joy we deserve and crave. The bright and wielding futures we strive and dream for. T

hrough four characters this warm future has been created, strong glances, resilient faces, the idea is to have people see themselves in the figures and imagine what their future will be.

Ageless and present. They are here, they are possible and they are us!

Liverpool based illustrator and artist Sumuyya Khader works in a multiplicity of ways within the sector including with major institutions, independent projects, publishers, social enterprises and artist-led groups.

Her practice is a combination of illustration, painting & print works that predominantly explore place and identity.

Recent projects have included establishing Granby Press, a community print shop built as a resource for the local community to print zines, newsletters, flyers and artworks.

Her first solo show ‘Always Black, Never Blue’ opened at Bluecoat Liverpool in October 2021 and her next show is part of a group exhibition Refractive Pool: Contemporary Painting in Liverpool opening at Walker Art Gallery in April 2022. In October 2020, Khader curated Celebrating Black Liverpool Artists, an outdoor exhibition on the facade of the Bluecoat as part of Liverpool City Council’s Without Walls programme, which celebrated the work of 5 Liverpool artists and highlighted the lack of visibility for the work of Black women in the city.

Sumuyya's design responds to the theme ‘Reimagine the Future’, which gives us free rein to imagine the society we can create when we have a full understanding of our shared history; the place the UK can hold in the world when it acknowledges its past; and who we can be as people and a country when we give full dignity to all.

Characters reimagined and futures unknown.

This piece is a colourful representation of all that is colourful and Black. The moments of joy we deserve and crave. The bright and wielding futures we strive and dream for. T

hrough four characters this warm future has been created, strong glances, resilient faces, the idea is to have people see themselves in the figures and imagine what their future will be.

Ageless and present. They are here, they are possible and they are us!

Liverpool based illustrator and artist Sumuyya Khader works in a multiplicity of ways within the sector including with major institutions, independent projects, publishers, social enterprises and artist-led groups.

Her practice is a combination of illustration, painting & print works that predominantly explore place and identity.

Recent projects have included establishing Granby Press, a community print shop built as a resource for the local community to print zines, newsletters, flyers and artworks.

Her first solo show ‘Always Black, Never Blue’ opened at Bluecoat Liverpool in October 2021 and her next show is part of a group exhibition Refractive Pool: Contemporary Painting in Liverpool opening at Walker Art Gallery in April 2022. In October 2020, Khader curated Celebrating Black Liverpool Artists, an outdoor exhibition on the facade of the Bluecoat as part of Liverpool City Council’s Without Walls programme, which celebrated the work of 5 Liverpool artists and highlighted the lack of visibility for the work of Black women in the city.

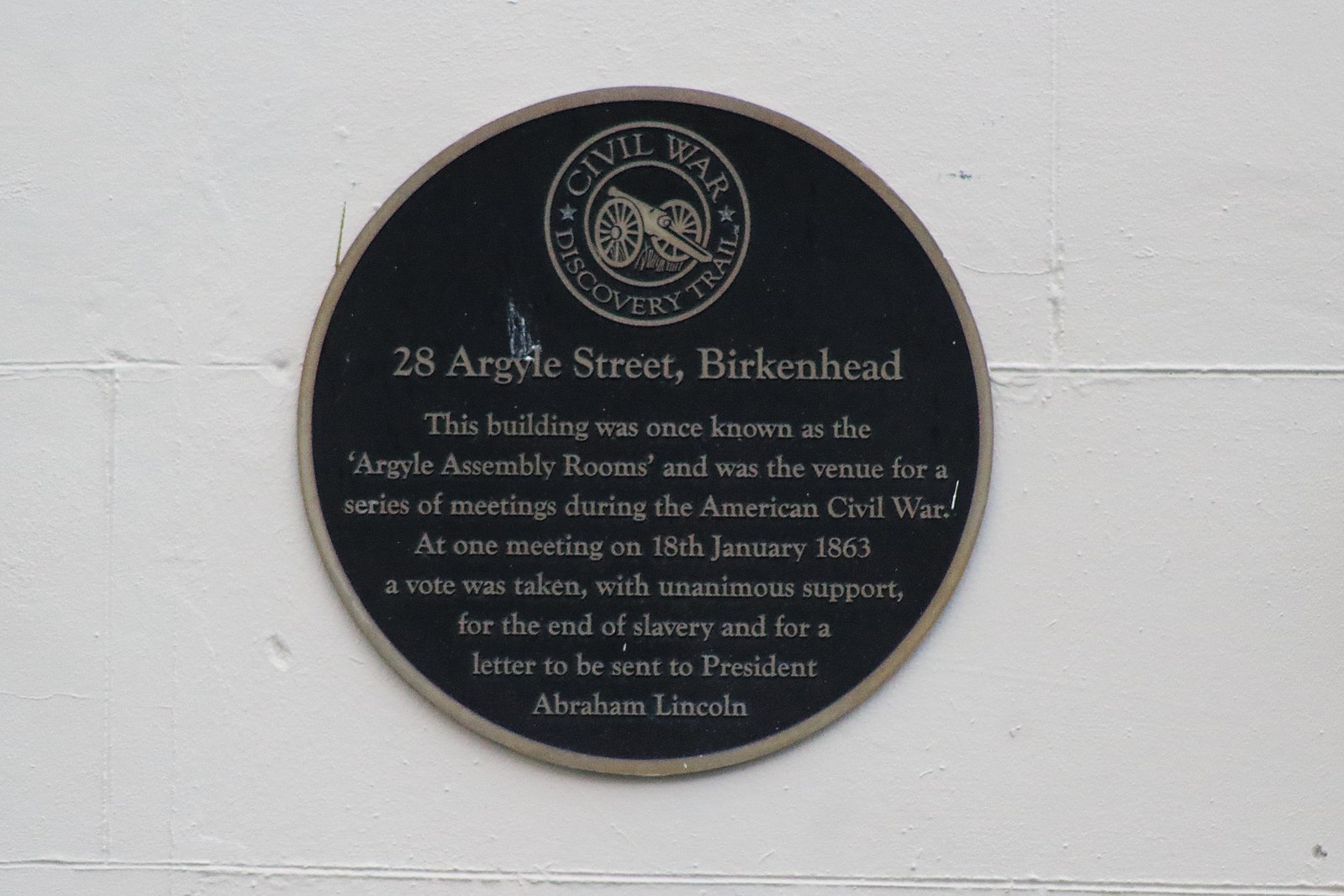

| 28 Argyle Street, Birkenhead CH41 6AE |

Although Birkenhead was home to supporters of the Confederacy, most notably John Laird, it was also a meeting place for the town's abolitionists. There is a plaque on the former Argyle Assembly Rooms, at 28-30 Argyle Street noting that during the American Civil War the buildings were an important meeting place for the anti-slavery lobby. 'At a meeting, on 18th January 1863, a vote was taken pledging unanimous support for the end of slavery and a letter to this effect was sent to President Lincoln.'

Image by Phil Nash 2018 CC BY-SA 4.0

Although Birkenhead was home to supporters of the Confederacy, most notably John Laird, it was also a meeting place for the town's abolitionists. There is a plaque on the former Argyle Assembly Rooms, at 28-30 Argyle Street noting that during the American Civil War the buildings were an important meeting place for the anti-slavery lobby. 'At a meeting, on 18th January 1863, a vote was taken pledging unanimous support for the end of slavery and a letter to this effect was sent to President Lincoln.'

Image by Phil Nash 2018 CC BY-SA 4.0

| Liscard Rd, Wallasey CH44 0BS |

Sir John Tobin(1762-1851), was a slave ship captain, owner and privateer. His knowledge of West Africa and its trading routes led him into the very lucrative palm oil business after the slave trade was abolished by the British in 1807. The links he had created with African slavers such as the Old Calabar merchant, Duke Ephraim, during his slave-trading days were put to further profitable use in acquiring this 'legitimate' African trade item, although it would almost certainly have been enslaved people who would have harvested and processed the nuts on the palm plantations of what is now south-eastern Nigeria. That same year he was elected Mayor of Liverpool and in 1820 was knighted by George IV on his accession to the throne. In 1835 Tobin moved to the Wirral to the newly built Liscard Hall and on the outskirts of the estate, he erected St. John's Church, Liscard. The grounds of Liscard Hall became Wallasey's Central Park when the local corporation bought the estate in the final years of the nineteenth century and the house itself would become Liscard Science and Art College.

(Image By Sue Adair, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Sir John Tobin(1762-1851), was a slave ship captain, owner and privateer. His knowledge of West Africa and its trading routes led him into the very lucrative palm oil business after the slave trade was abolished by the British in 1807. The links he had created with African slavers such as the Old Calabar merchant, Duke Ephraim, during his slave-trading days were put to further profitable use in acquiring this 'legitimate' African trade item, although it would almost certainly have been enslaved people who would have harvested and processed the nuts on the palm plantations of what is now south-eastern Nigeria. That same year he was elected Mayor of Liverpool and in 1820 was knighted by George IV on his accession to the throne. In 1835 Tobin moved to the Wirral to the newly built Liscard Hall and on the outskirts of the estate, he erected St. John's Church, Liscard. The grounds of Liscard Hall became Wallasey's Central Park when the local corporation bought the estate in the final years of the nineteenth century and the house itself would become Liscard Science and Art College.

(Image By Sue Adair, CC BY-SA 2.0)

| 23 King George's Dr, Bebington, Wirral CH62 5DX |

The industrial model village of Port Sunlight was built by William Lever in the late 19th-century, for the workers at his soapmaking factory, Lever Brothers. Lever believed that happy, healthy workers made his business more productive. Here, they received good quality housing and had access to social, cultural, and welfare amenities. While Lever Brothers workers in Port Sunlight benefited from positive living conditions, others elsewhere did not. Lever wanted to source soapmaking ingredients, like kopra and palm oil, as cheaply as possible. So, in the early 20th century, he set up plantations in countries including the former Belgian Congo. Initially, Lever had intended one of the worker villages there, which he named “Leverville” (modern-day Lusanga), to be like Port Sunlight. However, the plantations soon became places where Congolese communities suffered enforced labour practices and racial violence. To learn more, read Port Sunlight Village Trust’s research booklet, Racism, the Belgian Congo, and William Lever.

(Image By Rich Daley, CC BY-SA 2.0)

The industrial model village of Port Sunlight was built by William Lever in the late 19th-century, for the workers at his soapmaking factory, Lever Brothers. Lever believed that happy, healthy workers made his business more productive. Here, they received good quality housing and had access to social, cultural, and welfare amenities. While Lever Brothers workers in Port Sunlight benefited from positive living conditions, others elsewhere did not. Lever wanted to source soapmaking ingredients, like kopra and palm oil, as cheaply as possible. So, in the early 20th century, he set up plantations in countries including the former Belgian Congo. Initially, Lever had intended one of the worker villages there, which he named “Leverville” (modern-day Lusanga), to be like Port Sunlight. However, the plantations soon became places where Congolese communities suffered enforced labour practices and racial violence. To learn more, read Port Sunlight Village Trust’s research booklet, Racism, the Belgian Congo, and William Lever.

(Image By Rich Daley, CC BY-SA 2.0)

| L21 3TW |

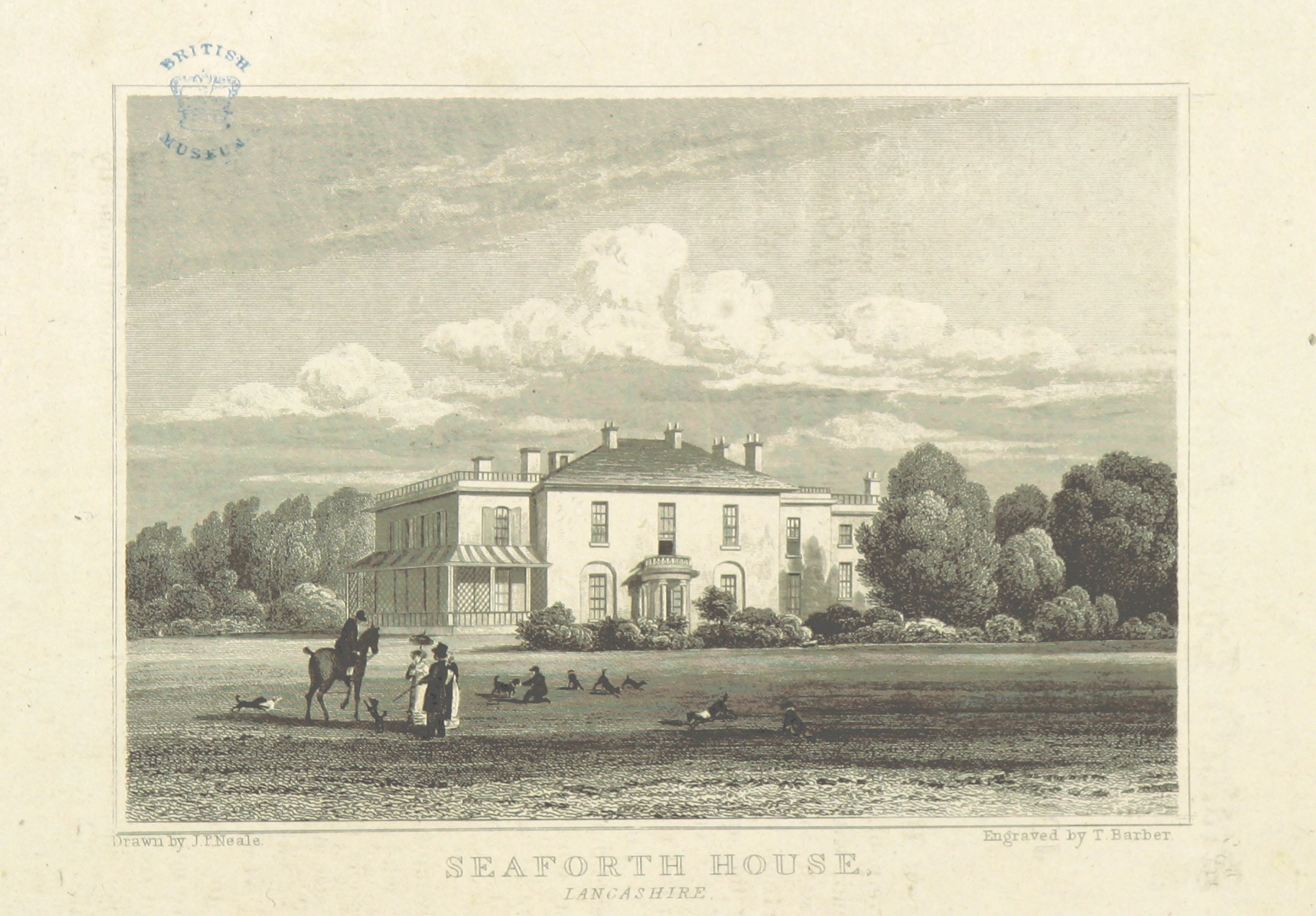

John Gladstone was Scottish merchant, slave owner, politician and the father of the British Prime Minister William Gladstone. Through his commercial activities he acquired several large plantations in Jamaica and Guyana that were worked initially by enslaved Africans. The Demerara Rebellion of 1823, a slave revolt centred on his estates was brutally crushed by the military. The extent of his ownership of slaves was such that after slavery was abolished in 1833, he received the largest of all compensation payments made by the Slave Compensation Commission.

John Gladstone built his home Seaforth House in 1813 on 100 acres of Litherland Marsh, but the family never really settled. In 1830, they left Seaforth House and returned to his native Scotland. Seaforth House was eventually demolished in 1881 and nothing now remains. It was located on what is today Princess Way, Seaforth.

(Image By John Preston Neale )

John Gladstone was Scottish merchant, slave owner, politician and the father of the British Prime Minister William Gladstone. Through his commercial activities he acquired several large plantations in Jamaica and Guyana that were worked initially by enslaved Africans. The Demerara Rebellion of 1823, a slave revolt centred on his estates was brutally crushed by the military. The extent of his ownership of slaves was such that after slavery was abolished in 1833, he received the largest of all compensation payments made by the Slave Compensation Commission.

John Gladstone built his home Seaforth House in 1813 on 100 acres of Litherland Marsh, but the family never really settled. In 1830, they left Seaforth House and returned to his native Scotland. Seaforth House was eventually demolished in 1881 and nothing now remains. It was located on what is today Princess Way, Seaforth.

(Image By John Preston Neale )

| The Liver Hotel, 137 South Road, Waterloo L22 0LT |

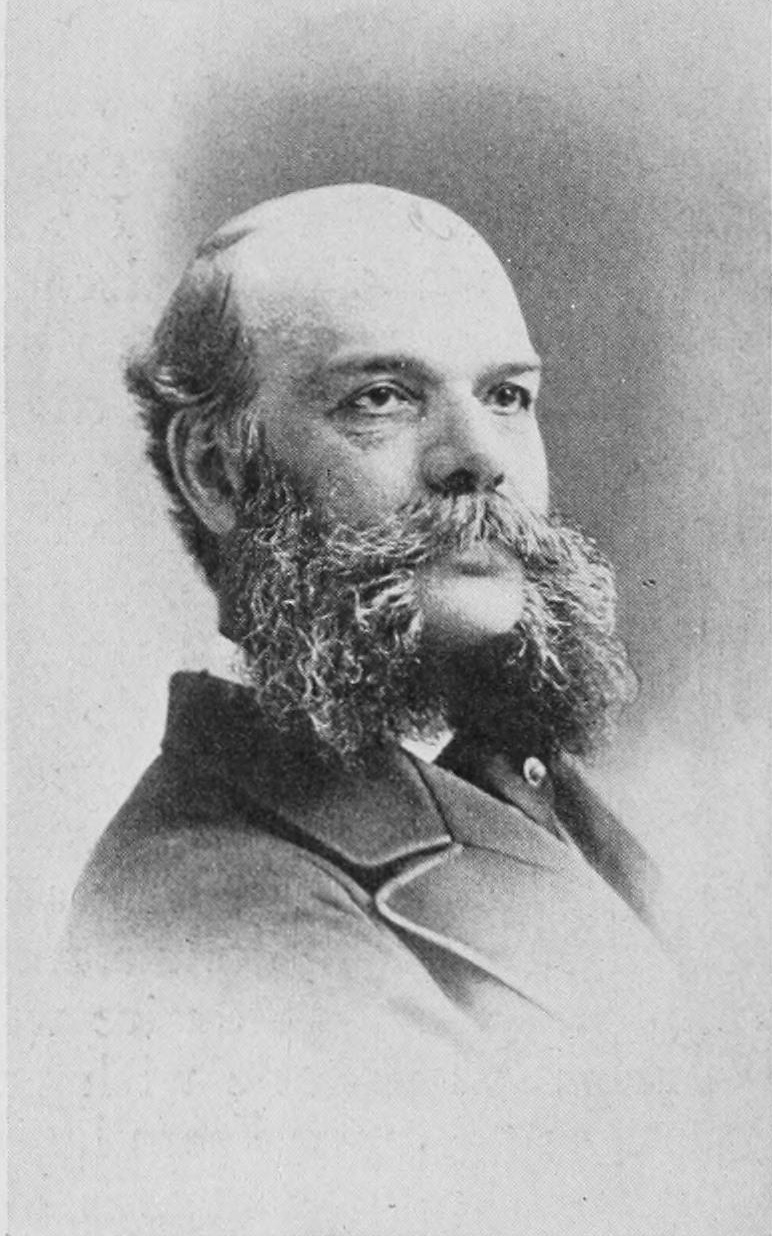

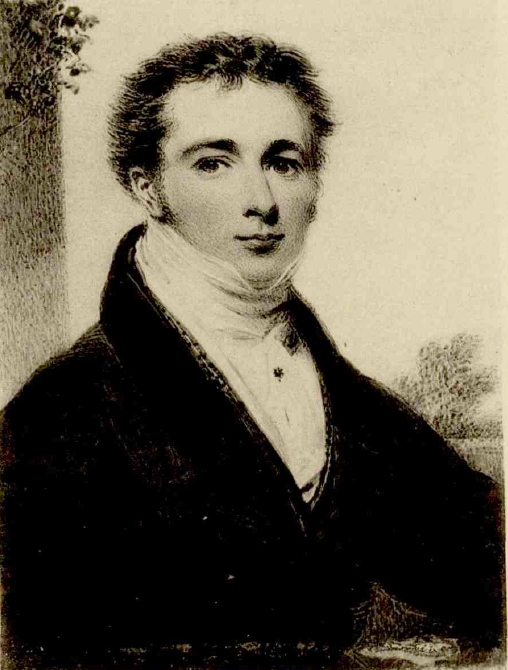

In 1861, Waterloo was at the centre of a spy ring created by an American secret agent called James Dunwoody Bulloch. Bulloch was a captain in the army of the Confederate States of America and had been sent to England with a mission to raise money for the cause, and commission ships to break the blockade of Confederate held ports.

He arrived with $1 million to commission 6 vessels, including the famed CSS Alabama. He chose Liverpool as the centre of operations due to the strong cotton links with the southern states and because Lairds shipbuilders were nearby.

When the Confederate cause was lost in 1865, Bulloch was branded a traitor, with a warrant for his arrest for treason. Forced to live in exile from his beloved home in Georgia, Captain Bulloch spent the rest of his days working as a cotton merchant, living in Waterloo and Liverpool where he died in 1901. He was never pardoned by the US Government.

Image By Unknown photographer - Roosevelt, Theodore (1913) Theodore Roosevelt; An Autobiography, The Macmillan Company, Public Domain

In 1861, Waterloo was at the centre of a spy ring created by an American secret agent called James Dunwoody Bulloch. Bulloch was a captain in the army of the Confederate States of America and had been sent to England with a mission to raise money for the cause, and commission ships to break the blockade of Confederate held ports.

He arrived with $1 million to commission 6 vessels, including the famed CSS Alabama. He chose Liverpool as the centre of operations due to the strong cotton links with the southern states and because Lairds shipbuilders were nearby.

When the Confederate cause was lost in 1865, Bulloch was branded a traitor, with a warrant for his arrest for treason. Forced to live in exile from his beloved home in Georgia, Captain Bulloch spent the rest of his days working as a cotton merchant, living in Waterloo and Liverpool where he died in 1901. He was never pardoned by the US Government.

Image By Unknown photographer - Roosevelt, Theodore (1913) Theodore Roosevelt; An Autobiography, The Macmillan Company, Public Domain

| Roby Rd, Huyton, Liverpool L16 3NA |

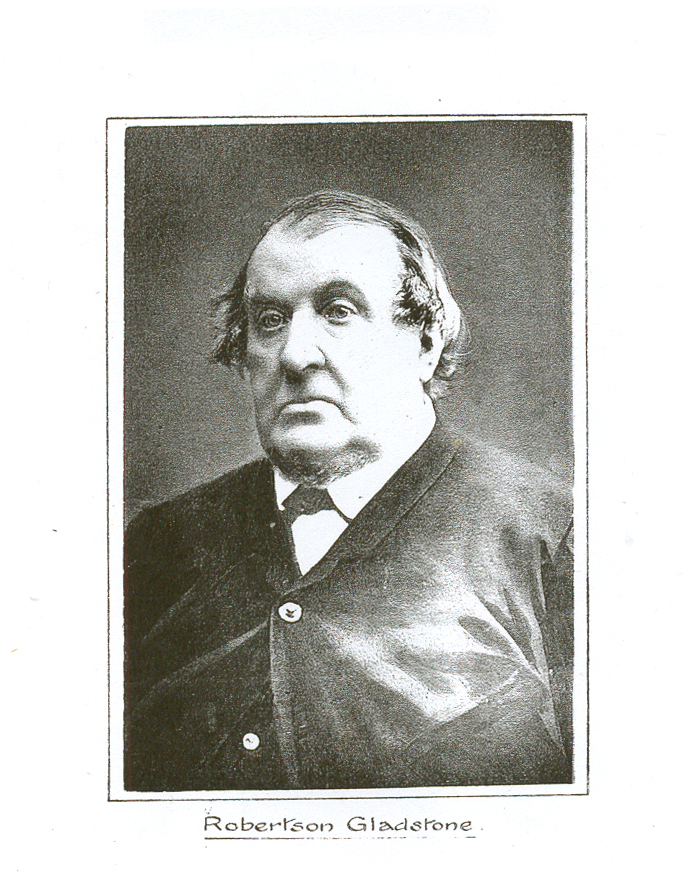

Court Hey Park, formerly the site of the National Wildflower Centre was the home of Robertson Gladstone, son of John Gladstone and brother of the future Prime Minister, William Ewart Gladstone. Robertson received over £21000 for the 393 slaves he had to free on his plantation in Demerara. He built the hall in 1836, around the time he would have received his compensation. The estate stayed in the Gladstone family until 1919, the house was demolished in 1956. Robertson also erected a fine town house in Abercromby Square. The twenty million pounds of compensation given to slave owners on the abolition of slavery in 1834 was the largest government bailout in British history, until the banking crash of 2008. The loan taken out by the treasury to pay the Gladstones and others at abolition was only finally paid off in 2015.

Many of Liverpool's finest public green spaces and buildings have a connection to merchants who traded in enslaved Africans and slave-produced goods.

(Image By Repository Liverpool Record Office Photographic album of Liverpool Town Council)

Court Hey Park, formerly the site of the National Wildflower Centre was the home of Robertson Gladstone, son of John Gladstone and brother of the future Prime Minister, William Ewart Gladstone. Robertson received over £21000 for the 393 slaves he had to free on his plantation in Demerara. He built the hall in 1836, around the time he would have received his compensation. The estate stayed in the Gladstone family until 1919, the house was demolished in 1956. Robertson also erected a fine town house in Abercromby Square. The twenty million pounds of compensation given to slave owners on the abolition of slavery in 1834 was the largest government bailout in British history, until the banking crash of 2008. The loan taken out by the treasury to pay the Gladstones and others at abolition was only finally paid off in 2015.

Many of Liverpool's finest public green spaces and buildings have a connection to merchants who traded in enslaved Africans and slave-produced goods.

(Image By Repository Liverpool Record Office Photographic album of Liverpool Town Council)

| Roby Rd, Huyton, Liverpool L36 4HD |

The name Bowring Park comes from the Bowring family who were tenants/owners of the estate. William Bowring held a firm stance against the revival of the African slave trade and this caused his popularity to decline in some circles. He gifted the park to the citizens of Liverpool in 1906 and the park was named Bowring Park in 1907. The links between this park and slavery are through a number of former tenants who either had ships or plantations that exploited slaves. Key names include:

(Image By Sue Adair, CC BY-SA 2.0)

The name Bowring Park comes from the Bowring family who were tenants/owners of the estate. William Bowring held a firm stance against the revival of the African slave trade and this caused his popularity to decline in some circles. He gifted the park to the citizens of Liverpool in 1906 and the park was named Bowring Park in 1907. The links between this park and slavery are through a number of former tenants who either had ships or plantations that exploited slaves. Key names include:

(Image By Sue Adair, CC BY-SA 2.0)

| WA10 3LL |

Although coal had been mined in the St Helens area since the sixteenth century it was not until the middle of the eighteenth century that the area would be transformed into one of the most significant regions of industrial Britain. This transformation was brought about by a large capital investment in transportation infrastructure,made possible by a group of wealthy merchants based in the booming town of Liverpool. On 5 June 1754, Liverpool Council determined that a survey of the Sankey Brook should take place to investigate whether it could be made navigable. All five of the merchants behind the campaign for the development of the Sankey Brook Navigation were involved in the slave trade: James Crosbie, John Ashton, Richard Trafford, Charles Goore and John Blackburne. All five were, or would become, prominent members of the Liverpool Corporation, holding high office in the town. Blackburne and Ashton would be key investors in the Sankey Brook Navigation, becoming the largest shareholders in the endeavour at its completion in 1757.

Although coal had been mined in the St Helens area since the sixteenth century it was not until the middle of the eighteenth century that the area would be transformed into one of the most significant regions of industrial Britain. This transformation was brought about by a large capital investment in transportation infrastructure,made possible by a group of wealthy merchants based in the booming town of Liverpool. On 5 June 1754, Liverpool Council determined that a survey of the Sankey Brook should take place to investigate whether it could be made navigable. All five of the merchants behind the campaign for the development of the Sankey Brook Navigation were involved in the slave trade: James Crosbie, John Ashton, Richard Trafford, Charles Goore and John Blackburne. All five were, or would become, prominent members of the Liverpool Corporation, holding high office in the town. Blackburne and Ashton would be key investors in the Sankey Brook Navigation, becoming the largest shareholders in the endeavour at its completion in 1757.

| WA9 4BB |

Hundreds of Afro-Caribbeans worked in British coal mines in the decades after the second world war. There were many black miners working in St Helens, including Mr George Street (1925-2001) a coal face worker, safety officer and first aider who worked at Sutton Manor Colliery from 1956-1985.

"Dream" is a 20 metre high sculpture located on the former site of Sutton Manor Colliery, designed by world-renowned and award-winning artist, Jaume Plensa.

The sculpture takes form of a young girl's head cast in white dolomite. Her eyes are closed in a dream-like state. Dream was commissioned by both ex-miners and St Helens Borough Council with the aim of reflecting the aspirations of the community. It was decided a mining monument was far from the wishes of the community and instead, a forward-looking piece to inspire future generations.

(Image By Christian Keenan ,CC BY-SA 3.0)

Hundreds of Afro-Caribbeans worked in British coal mines in the decades after the second world war. There were many black miners working in St Helens, including Mr George Street (1925-2001) a coal face worker, safety officer and first aider who worked at Sutton Manor Colliery from 1956-1985.

"Dream" is a 20 metre high sculpture located on the former site of Sutton Manor Colliery, designed by world-renowned and award-winning artist, Jaume Plensa.

The sculpture takes form of a young girl's head cast in white dolomite. Her eyes are closed in a dream-like state. Dream was commissioned by both ex-miners and St Helens Borough Council with the aim of reflecting the aspirations of the community. It was decided a mining monument was far from the wishes of the community and instead, a forward-looking piece to inspire future generations.

(Image By Christian Keenan ,CC BY-SA 3.0)

| WA12 9AQ |

The naming of ‘Earlestown’ comes from Hardman Earle (1792-1877). The Earle family included generations that profited from the trading and ownership of slaves and the Earle family amassed a wealth, earned from slavery-supported industries and plantations.

Hardman Earle’s great grandfather John Earle(1674-1749) traded in tobacco, sugar and iron goods and became Mayor of Liverpool in 1709. His youngest son William (1721-1788) captained a slave ship called Chesterfield from 1751 as well as part-owning other slaving vessels.

Hardman Earl inherited the family businesses, including a number of plantations. He was the director of the London and North Western Railway, and the town of Earlestown was named after him.

(Image By Desertarun - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=109052802)

The naming of ‘Earlestown’ comes from Hardman Earle (1792-1877). The Earle family included generations that profited from the trading and ownership of slaves and the Earle family amassed a wealth, earned from slavery-supported industries and plantations.

Hardman Earle’s great grandfather John Earle(1674-1749) traded in tobacco, sugar and iron goods and became Mayor of Liverpool in 1709. His youngest son William (1721-1788) captained a slave ship called Chesterfield from 1751 as well as part-owning other slaving vessels.

Hardman Earl inherited the family businesses, including a number of plantations. He was the director of the London and North Western Railway, and the town of Earlestown was named after him.

(Image By Desertarun - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=109052802)

Login or Register to track the Globes you visit for chance to win a FREE copy of The World Reimagined book!

Find Out More

Artist Globe |

Learning Globe |

Points of Interest |