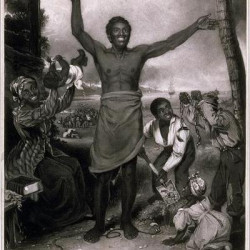

What industries in the UK benefited from the Trade in enslaved Africans?

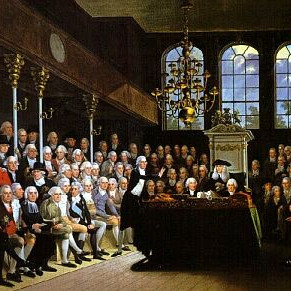

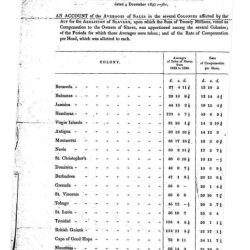

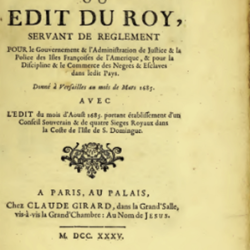

Britain was the most dominant between 1640 and 1807 when the British slave trade was abolished. Why was this?

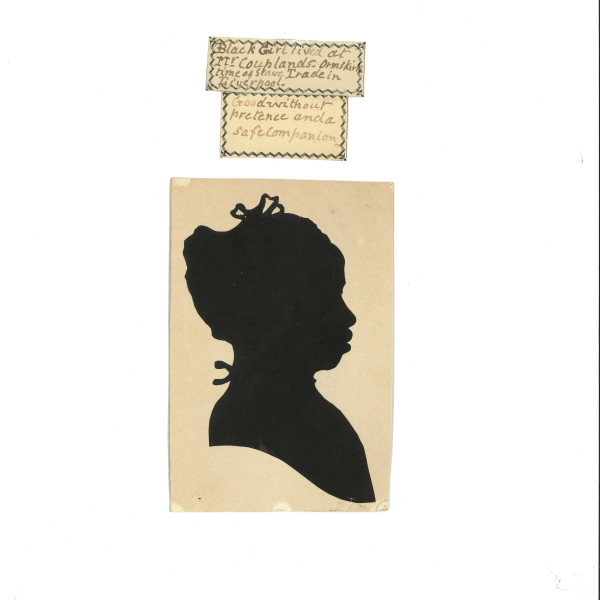

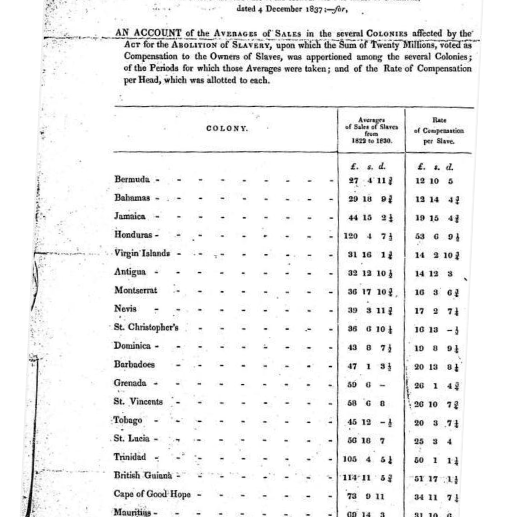

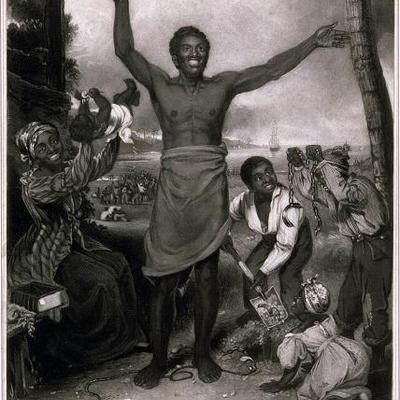

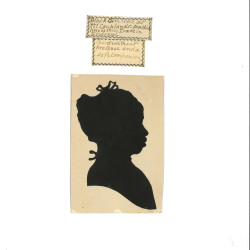

During 1761-1807 (46 years) an estimated profit of £8.8 million (£814 million today) was made by Britain's involvement in trafficking human beings to the Caribbean, North and South America. 3.8 million Africans landed as enslaved people.

It is easy to connect the profits with slavers and those who sailed between Europe, West Africa and the 'New World' but how did Britain benefit?

The web of those that supported - directly or indirectly - the trade in enslaved Africans is complex. The profits ran deep and fed many aspects of various British industries.

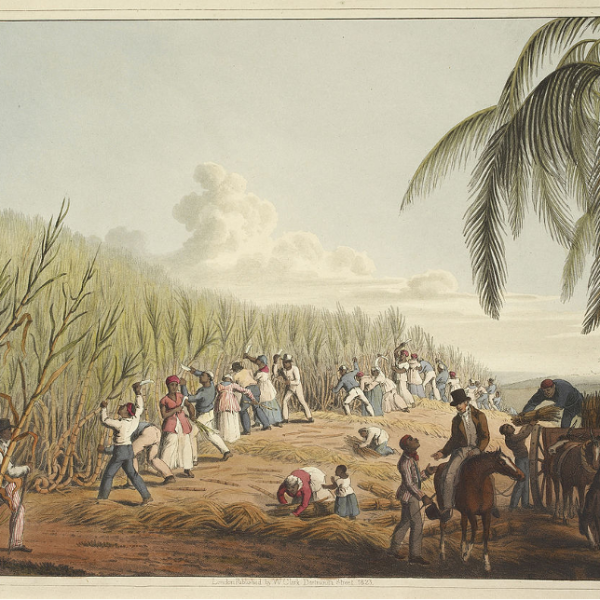

Shipbuilders, joiners and master craftsmen, sailmakers, ropemakers and metal-workers who made chains, manacles and other restraints used on slave ships profited from this trade. Others included those employed to service the Royal Navy, as naval ships were used to ensure the safety of the merchant navy, including slaving ships and exports to slave regimes.

Cloth producers, alcohol producers, gunmakers, producers of copper pans and other metal goods or manillas used to barter for enslaved people were always in demand. Trading also included Indian cotton and other goods imported by the East India Company.

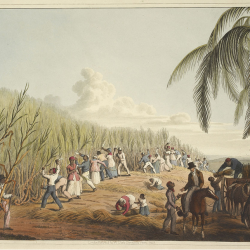

Food producers - beef and salted fish travelled well as well as producers of cheap and durable caps and clothing, makers of industrial equipment, tools and apparatus such as copper ‘stills’ for distilling sugar were also a necessary part of the industry that sprang up around the work enslaved people performed.

Candle-makers, booksellers, watchmakers, haberdashers, milliners, furniture makers, wine merchants, even snuff manufacturers, sugar refiners, cotton spinners and weavers, furniture makers were an integral part of proceedings.

So many people's livelihoods were interwoven with the abuse of enslaved Africans and their descendants, it is indeed a tangled web that was woven around the suffering of millions of enslaved Africans.

Previous Story

Previous Story