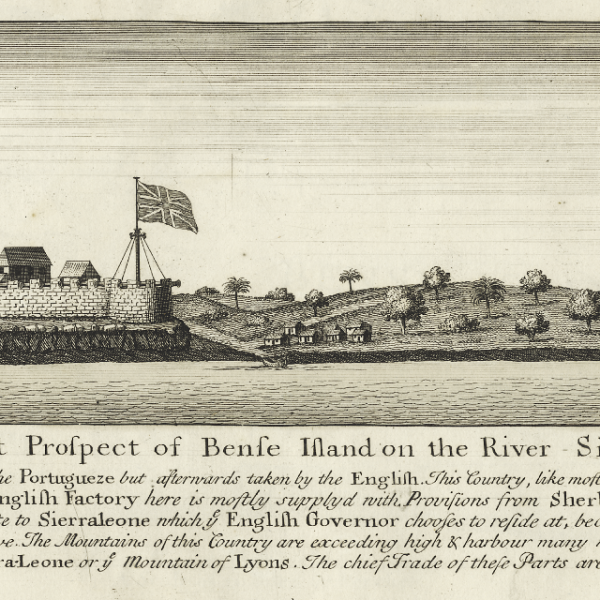

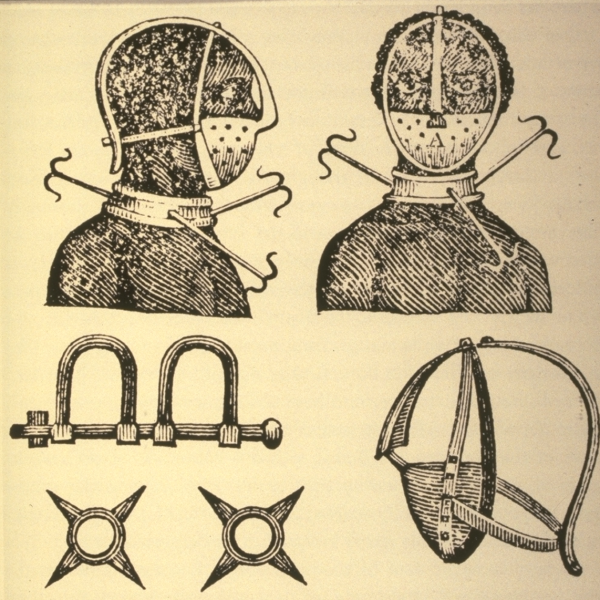

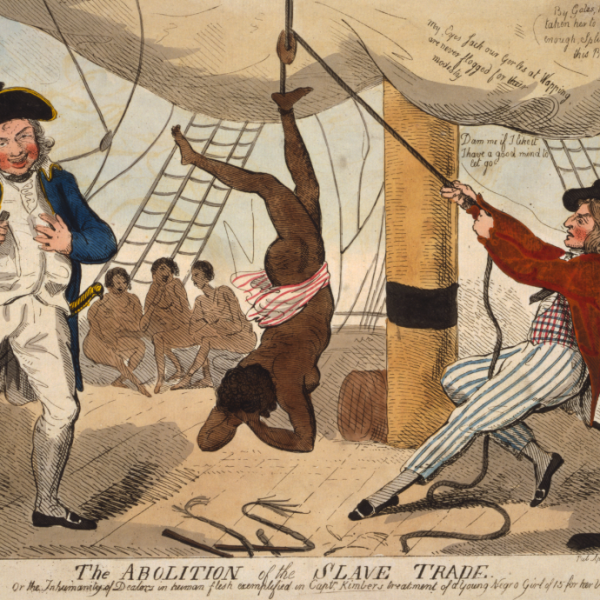

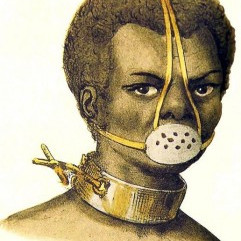

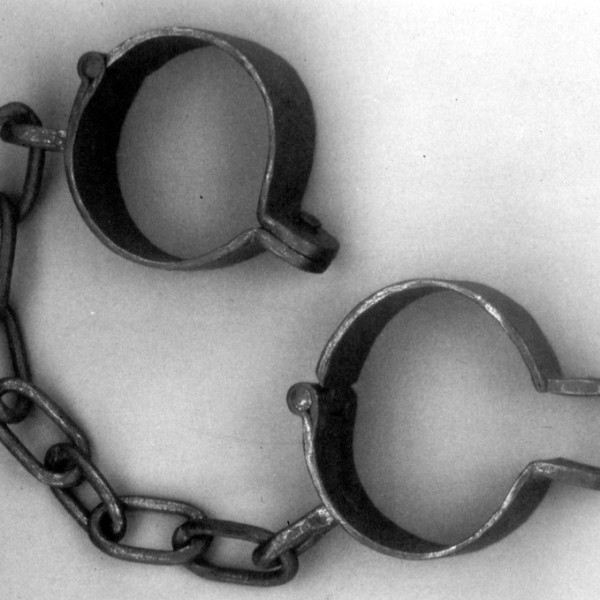

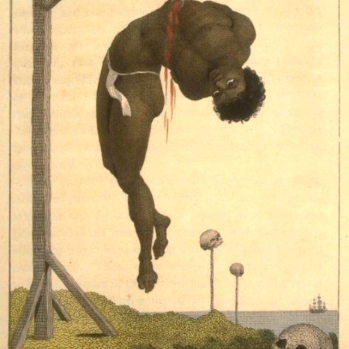

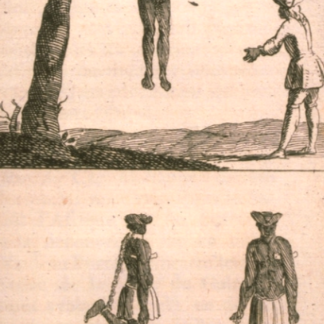

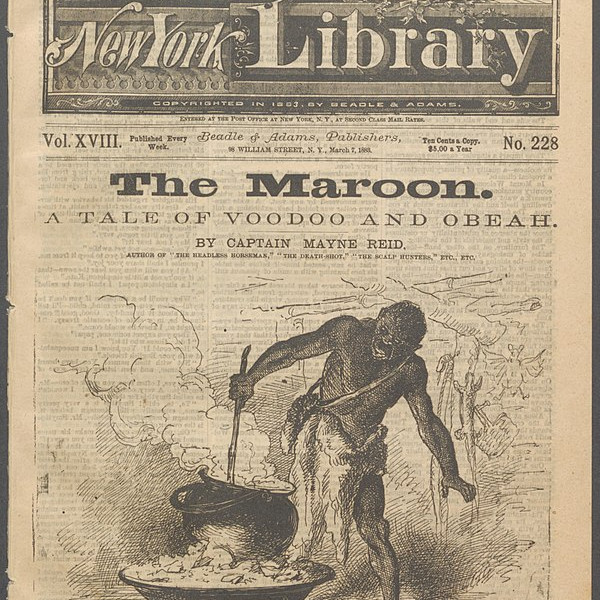

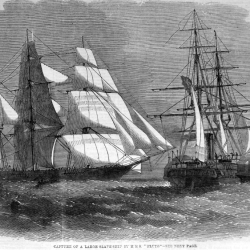

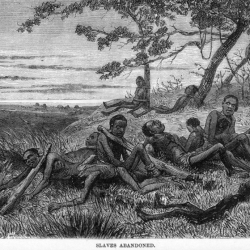

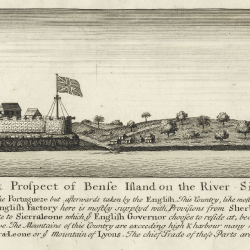

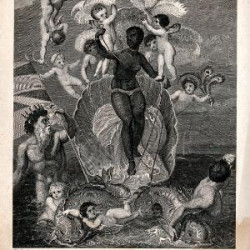

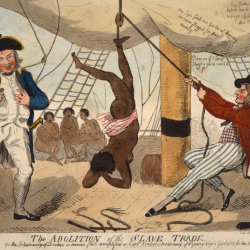

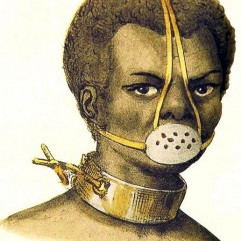

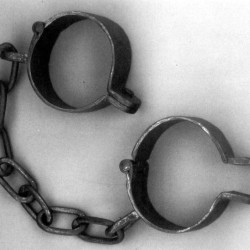

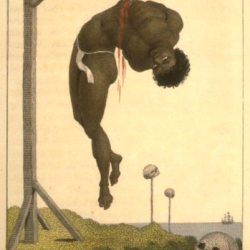

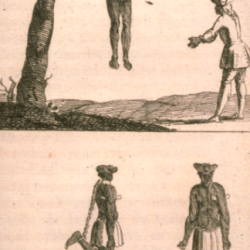

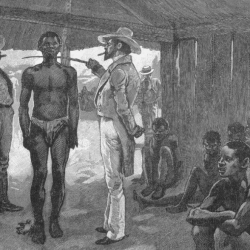

Even though laws passed in 1807 and 1833 outlawed trading and owning enslaved people throughout the British Empire, this did not stop merchants and planters from attempting to continue the practice. The illegal trade of enslaved people led to initiatives by the British government to intercept shipments on the seas. These actions helped liberate some of those captured.

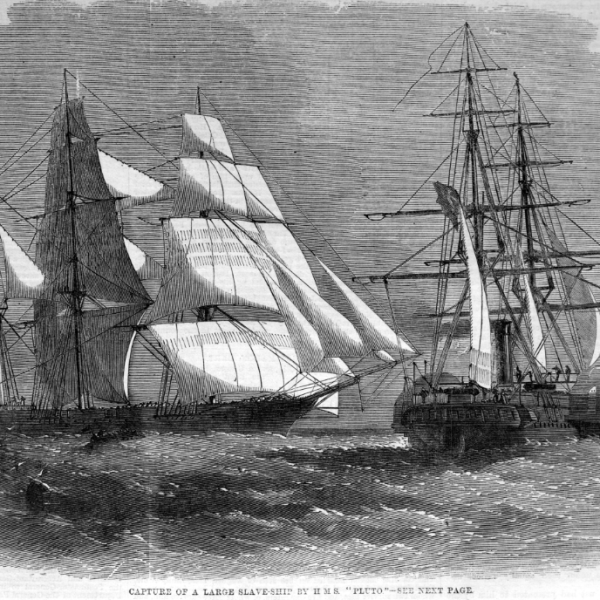

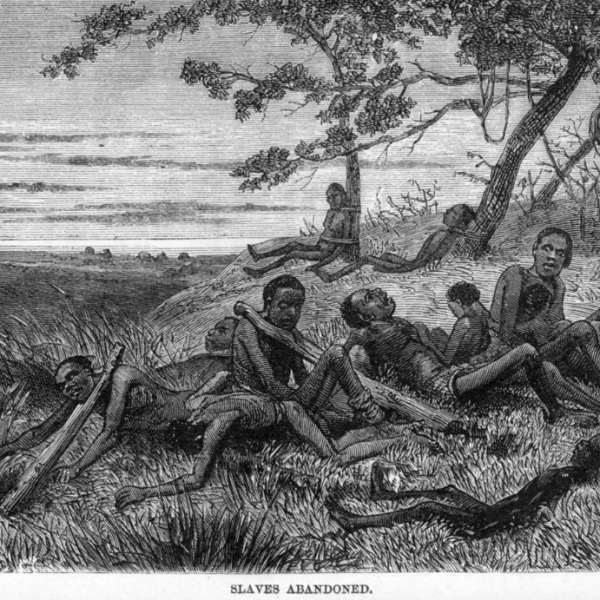

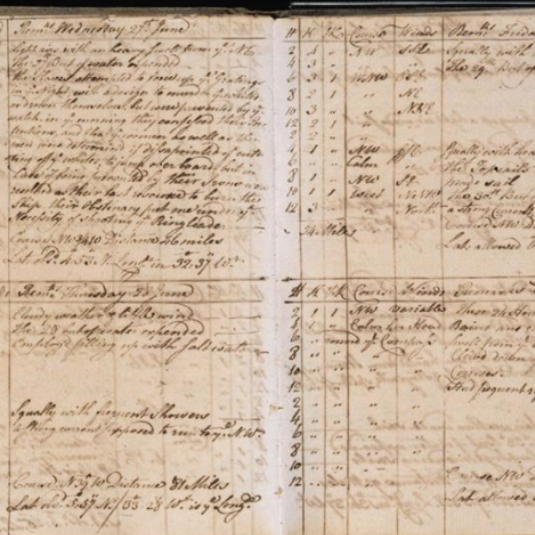

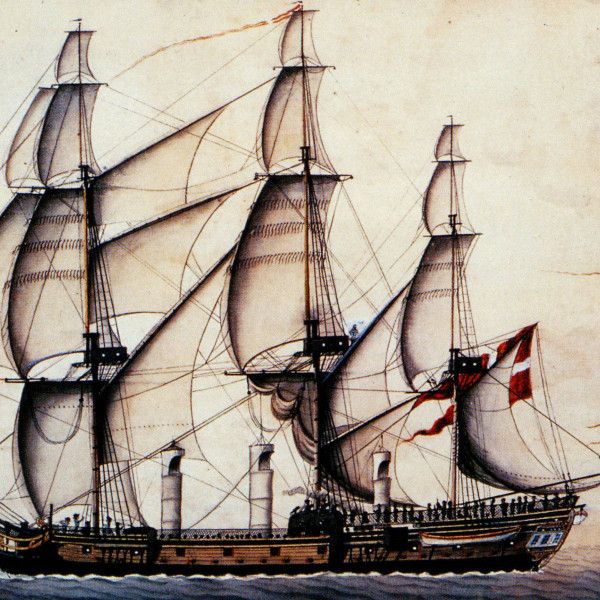

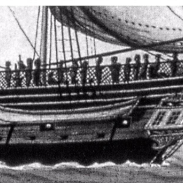

This is exactly what took place on 30 November, 1859. The HMS Pluto, a British ship used to apprehend ships carrying enslaved people, stopped the delivery of 874 people to Cuba by the vessel Orion. The Orion had departed from New York, taken on a cargo of enslaved people from Cabinda in Angola and was bound for St. Helena, before intending to sell the enslaved in Cuba.

The Orion tried to evade capture. Sighted at 'six or eight miles distant', as the Illustrated London News reported, a chase, which lasted about an hour and a half, resulted in members from the Pluto managing to board the Orion. The article goes on to tell us: 'On seeing the naval officers look down the main hatch, the liberated slaves sent up a most hearty cheer, which can never be forgotten by those who heard it.'

The piece provides evidence that, although enslavement was still an ongoing practice at this time, measures were being taken to try and curb the illicit trade of enslaved people.

Previous Story

Previous Story