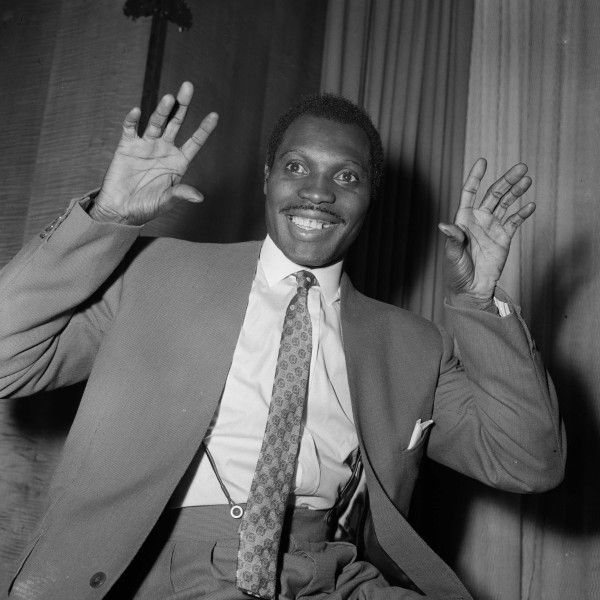

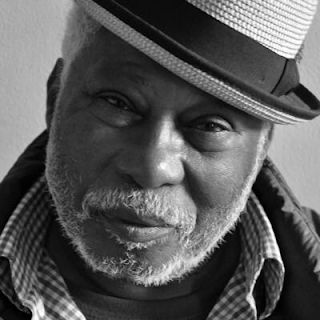

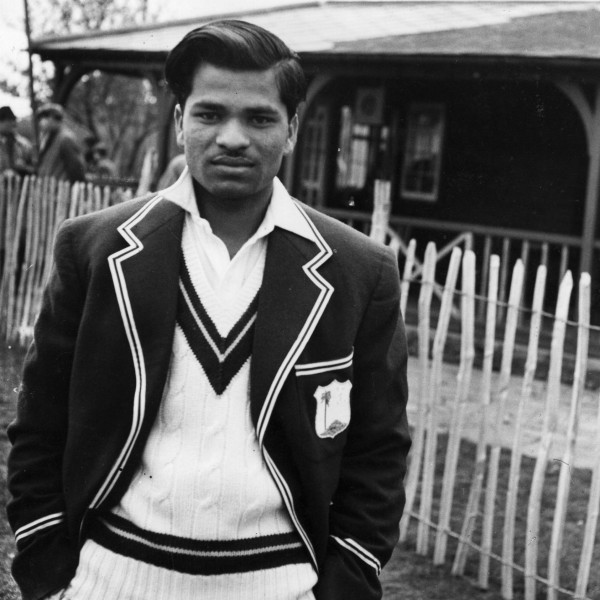

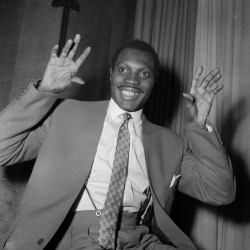

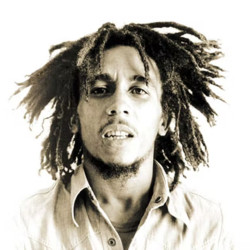

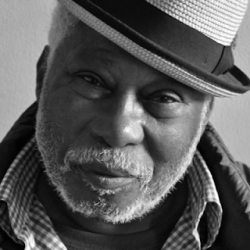

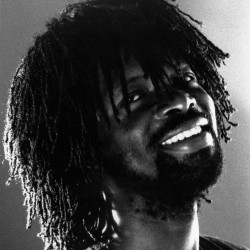

Aldwyn Roberts aka Lord Kitchener was born in Trinidad. His father helped him to develop his singing and guitar skills. His first job as a musician was playing guitar for labourers laying pipes in the San Fernando Valley. But after winning the Arima borough council's calypso competition five times between 1938 and 1942, there was no stopping him.

In 1943, he moved to Port of Spain where he met calypsonian, Growling Tiger, and took the name Lord Kitchener, later shortened to “Kitch”.

While on a tour to Jamaica with Lord Beginner (Egbert Moore) and Lord Woodbine (Harold Phillips), he heard about the Empire Windrush’s impending voyage to Britain. The three decided to book their passage along with hundreds of Caribbeans. He inadvertently came to symbolise the naive optimism on board when he performed the calypso song, London is the Place for Me, on the ship for Pathé News.

Kitch’s first residency was at a pub in Brixton, South London. He played a significant role in the popularity of calypso in the UK during the 1950s, becoming a regular on BBC Radio and having a residency at The Sunset Club in London. Later, he opened The Reno, a nightclub in Manchester.

Kitch returned to Trinidad in 1962, winning the country's infamous Road March competitions 10 times between 1963-1976; more so than any other calypsonian.

For 30 years, he ran his own calypso tent, Calypso Revue. Kitchener's compositions always proved popular as the chosen selections for steel bands to perform at the annual National Panorama competition during Trinidad Carnival.

Kitchener adopted the new soca genre on several albums from the mid-1970s. His most commercially successful song, and one of the earliest major soca hits, was ‘Sugar Bum Bum’ in 1978.

He is honoured with a statue in Port of Spain. A bust is also on display in Arima.

Previous Story

Previous Story