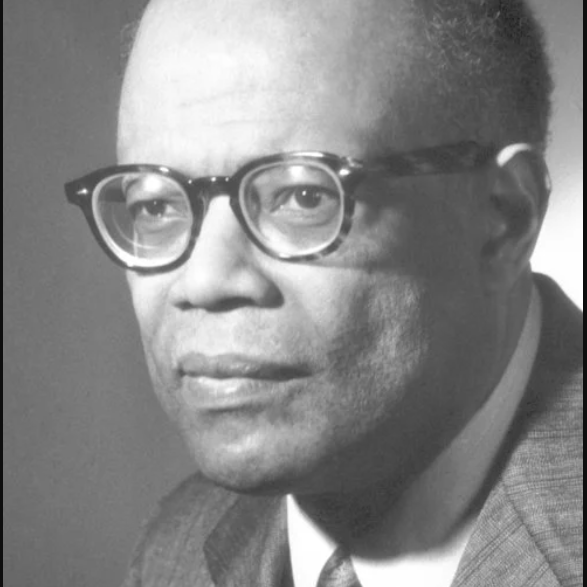

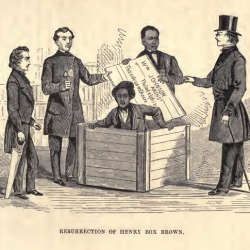

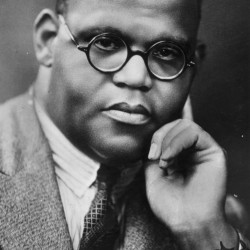

Henry ‘Box’ Brown was born enslaved in Richmond, Virginia, in 1816.

Returning from work one day in 1849 to find that his wife and children had been sold, he decided to orchestrate an unbelievably risky escape to free himself from the cruel reality of enslavement.

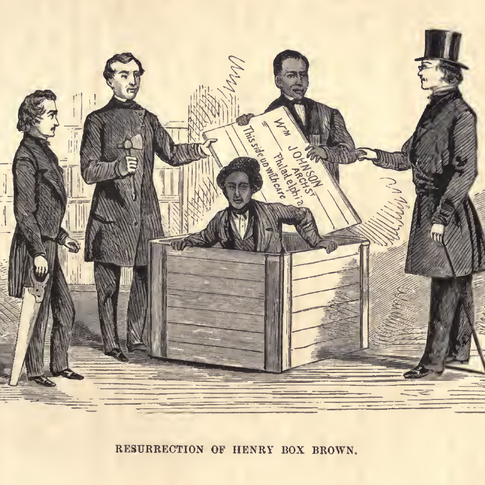

Brown paid for a box to be made, measuring one meter by one meter and just 60 centimeters wide. He squeezed himself into the box and posted himself from Virginia (where slavery was still in force) to Philadelphia (where slavery had been abolished two years before).

The box had holes so Brown could breathe and, with only some water and biscuits, he managed to survive the journey by wagon, boat and train. The journey took 72 hours and abolitionists in Philadelphia described how when they opened the box, ‘Brown clambered out and sung a freedom hymn: he was finally free.’

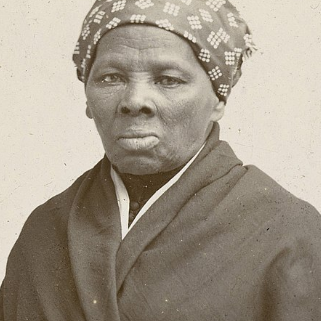

The passing of the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850 forced Brown to leave for the UK. This act meant formerly enslaved people - even if they were living free lives in the free north - could be captured and returned to their “owners”.

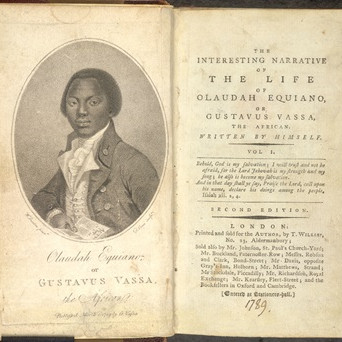

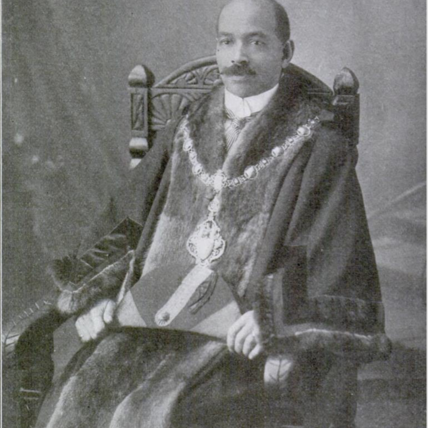

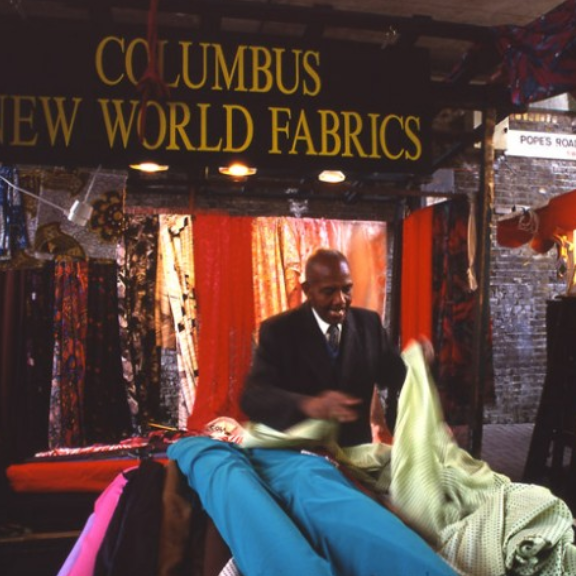

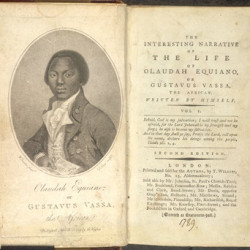

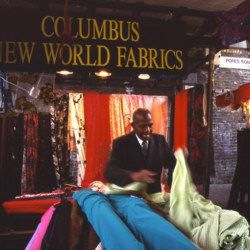

In England, Brown toured the country, performing his escape, as well as drawing from Harriet Beecher Stowe’s famous anti-slavery novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852), to create a panorama of enslavement on stage. Brown published the first edition of his autobiography in 1849. After marrying an English woman, he returned to America in 1875 and continued performing until his death in 1897.

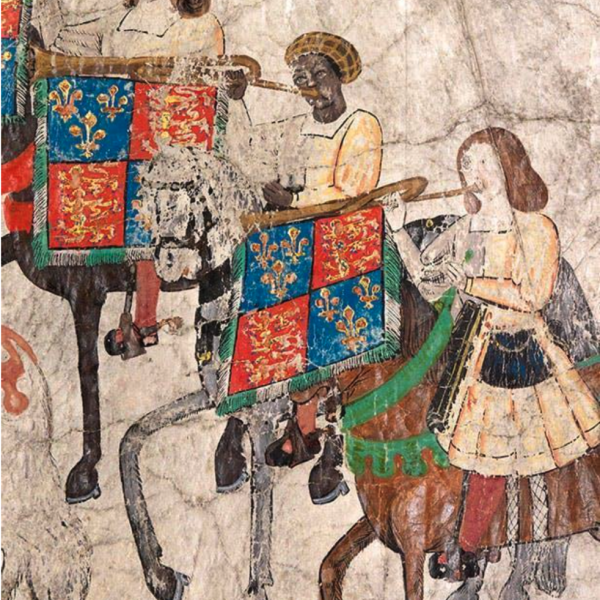

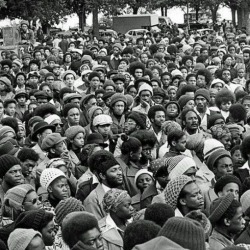

The story of Henry ‘Box’ Brown is an example of people using their intelligence and creativity to flee the most appalling circumstances. Stories such as this are key to our understanding of the history of enslavement. Enslaved people were not passive victims, they were integral to the political processes of abolition in the UK and put their intellectual, creative and artistic weight behind the movement.

Previous Story

Previous Story