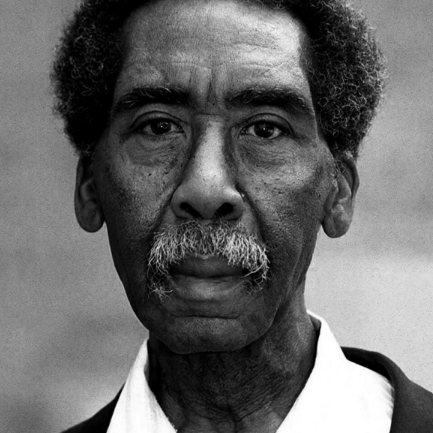

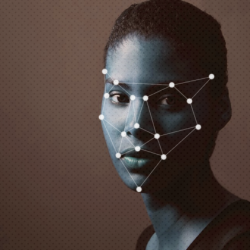

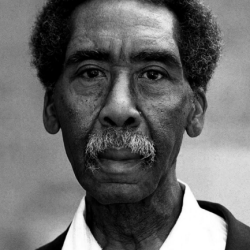

In UK workplaces, it is illegal to discriminate against people on the grounds of their race, gender, sexuality or religion. However, in 2022, it is not yet illegal to discriminate against someone because of their hair. This means that while it wouldn’t be right, it is still possible for Black people to be penalised at work or at school for wearing their hair in a natural, afro hairstyle.

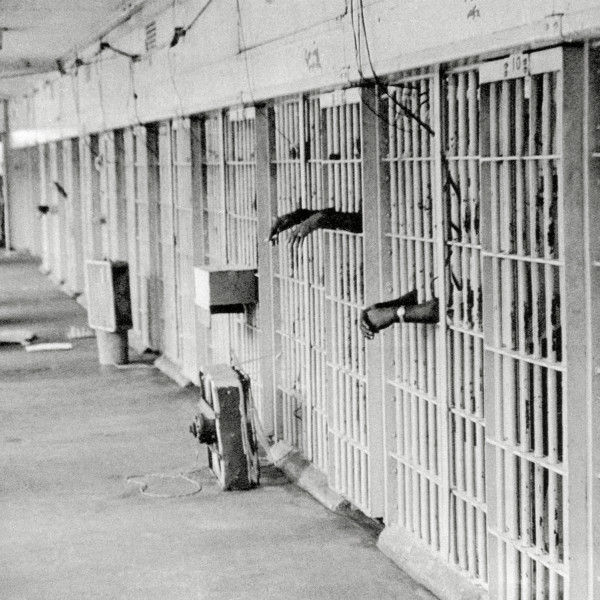

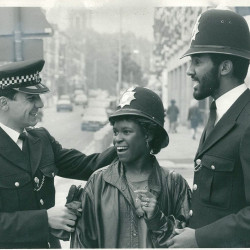

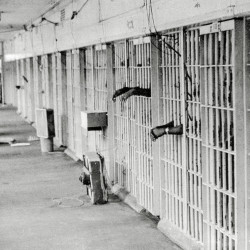

In fact, Black people in workplaces and schools face regular and routine discrimination and unwanted attention because of their hair, which is often seen as “exotic”. This can be deeply upsetting, and contributes heavily to feelings of otherness and isolation at work or in school. People have been dismissed or even suspended from work or school, and not allowed to return until their hair was more compliant with policy.

Often when people are penalised, they are told that Black hair is not “professional”, that it is messy, or even distracting. These prejudiced ideas that victimise Black people are rooted in the unfortunately pervasive and deep-seated societal ideal that white features are the standard, and are therefore held up as more desirable, professional and acceptable.

In 2020, author and presenter Emma Dabiri called for discrimination against hair to be classed as racism under the UK Equality Act, and therefore made illegal. While changes to law have yet to materialise, there are initiatives such as the Halo Code, which implores workplaces and schools to commit to respecting and celebrating afro hairstyles.

Whether it’s unwanted contact, comments, or even discriminatory rules that victimise Black hairstyles, schools and workplaces can be rife with potential difficulties. This can amount to pressure to straighten, hide or change one’s hair to be more accepted, less harassed and less at risk of prejudice.

Previous Story

Previous Story