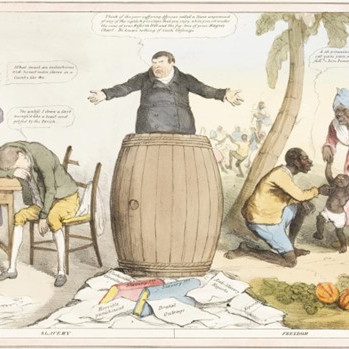

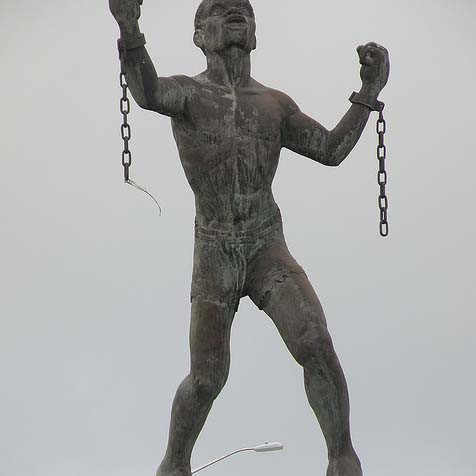

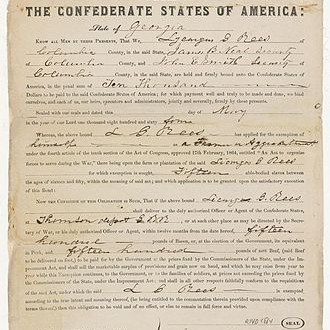

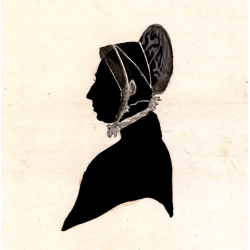

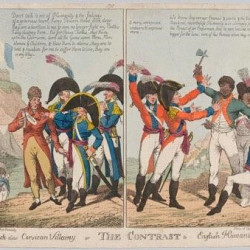

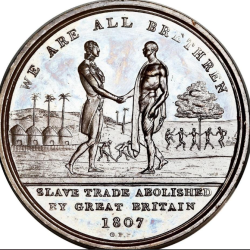

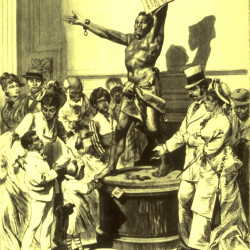

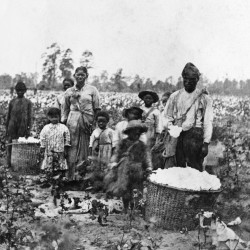

Nearly two decades after Britain’s legal abolition of the Transatlantic Trade in Enslaved Africans, Elizabeth Heyrick of Leicester condemned the continuing use of enslaved labour in its Caribbean colonies. In a pamphlet first disseminated across Britain and the United States in 1824, Heyrick provocatively questioned her country’s intentions as a “friend of emancipation, or of perpetual slavery,” and presented pro-emancipation position that challenged leading male abolitionists.

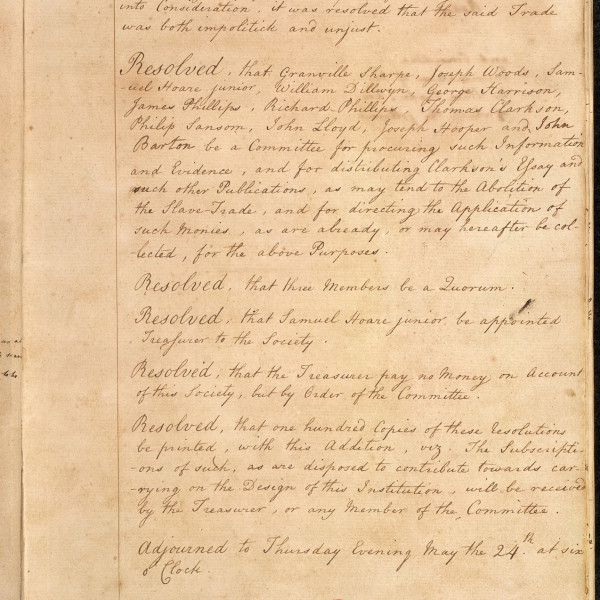

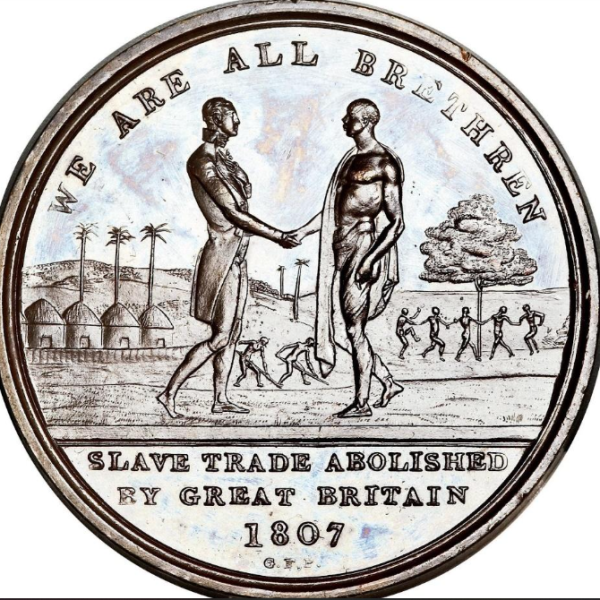

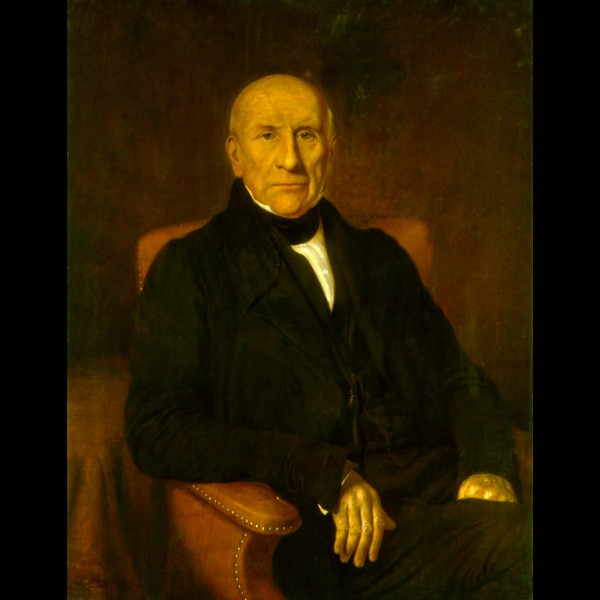

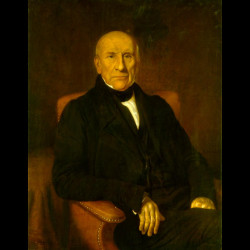

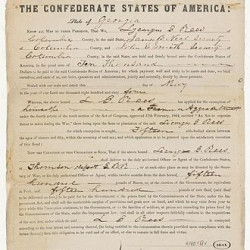

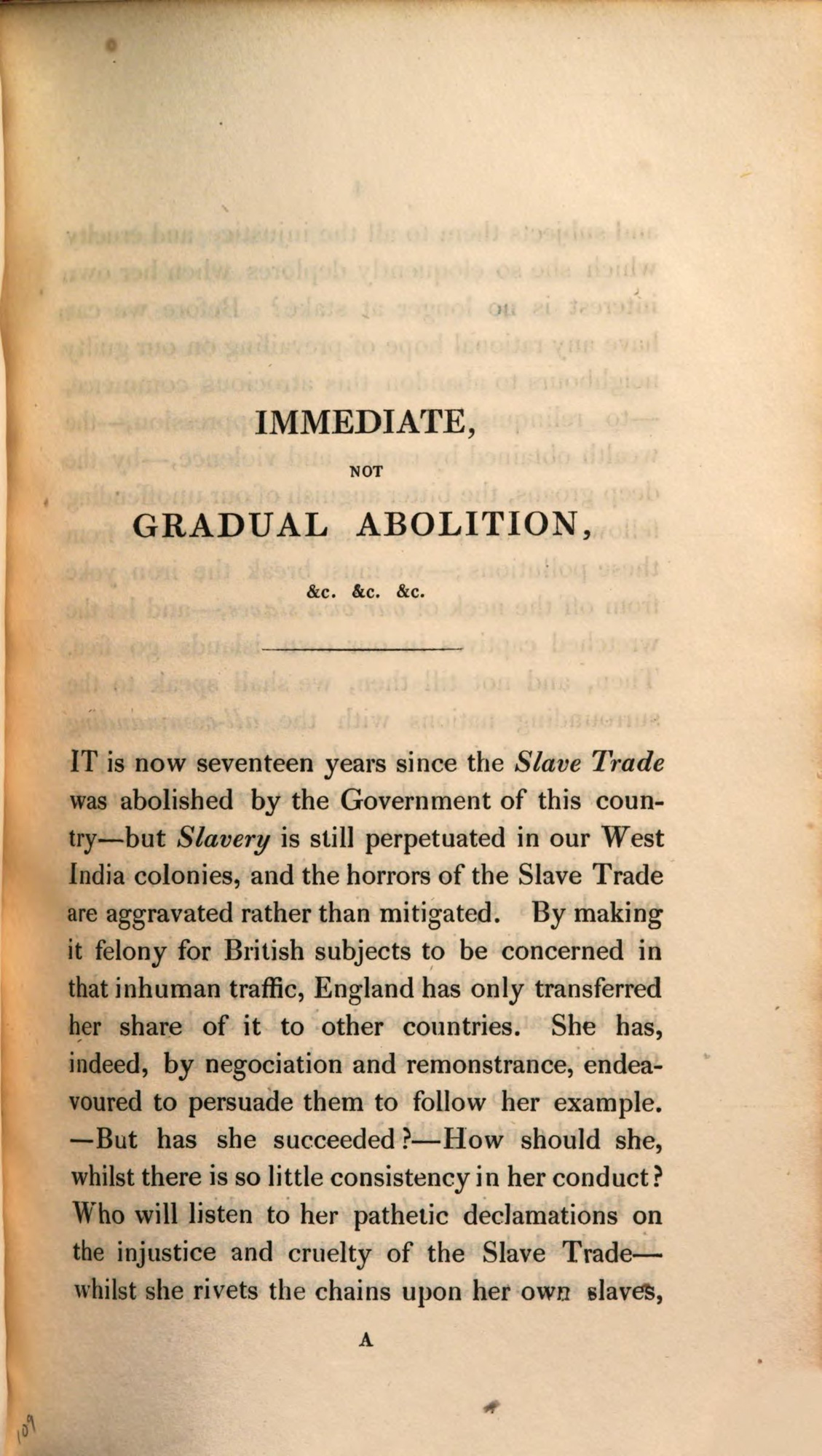

Her pamphlet Immediate, not Gradual Abolition (1824) criticised leading anti-slavery figures of the time for being too "polite" and “accommodating” of plantation owners in the Caribbean. Heyrick campaigned for the immediate abolition of colonial slavery, rather than the gradual approach favoured by William Wilberforce, Thomas Clarkson and other abolitionists after the abolition of Britain’s involvement in the Transatlantic Trade in Enslaved Africans in 1807, citing its privileging of planters’ interests over Black freedom.

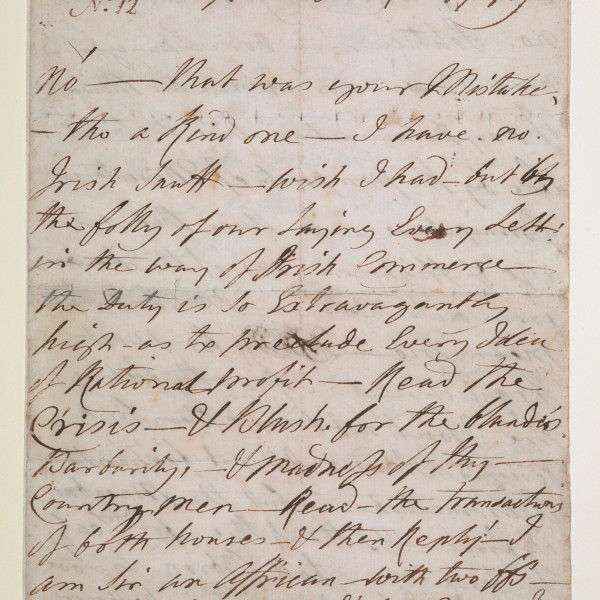

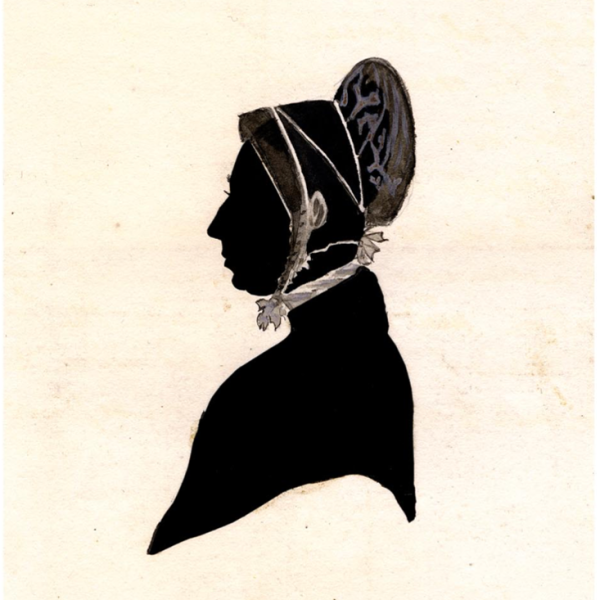

Born in 1769, Heyrick grew up reading works of revolutionaries and religious dissenters. Her calling to social reform sharpened after her husband’s death in 1795. A devoted Quaker, Heyrick renounced the material world and committed herself to activism, becoming a member of the Society of Friends. Heyrick’s overriding passion was for the abolition of slavery in the British colonies, something she believed, ‘in which we are all implicated; we are all guilty.’

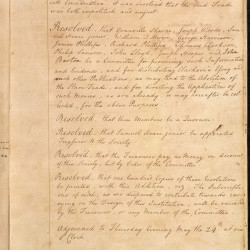

Immediate, not Gradual Abolition was widely distributed at anti-slavery meetings across the UK in the 1820s and was influential in shifting public opinion to support the cause of abolition. The pamphlet also sold thousands of copies in the USA.

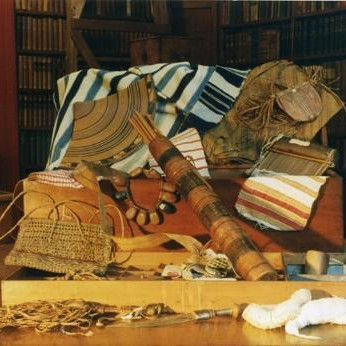

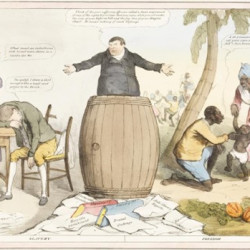

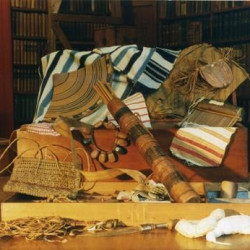

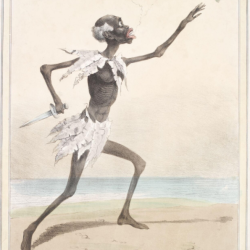

Women’s exclusion from Parliament did not dissuade Heyrick from pursuing alternative avenues in support of the abolitionist cause. Alongside the Birmingham Ladies Society for the Relief of Negro Slaves, Heyrick canvassed shops, promoting a successful boycott of sugar grown by slave labour, and collaborated on a women’s anti-slavery periodical, The Hummingbird. Wilberforce disapproved of the women’s community-based efforts, describing the Ladies’ public campaign as “unsuited to the female character.”

By 1830 there were more than 70 women’s anti-slavery societies in existence and they became an influential force in the abolitionist movement.

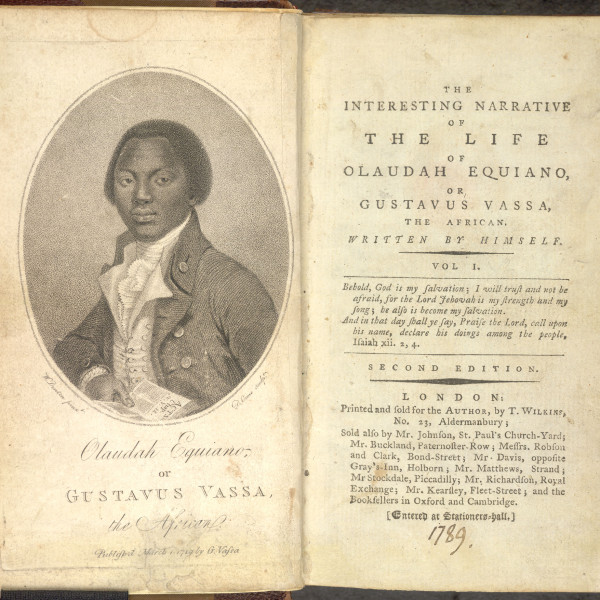

Heyrick died in October 1831, two years before the passage of the Abolition Act. Her contributions to abolition required a two-fold effort: one that challenged gradual emancipation while operating in a society that discouraged women’s political intervention. Her absence in popular narratives of British abolitionism reflects a wider eclipse of the contributions of women, people of colour, and the unfree people in the long struggle to end the enslavement of Africans.

Previous Story

Previous Story

The British Library

The British Library